Explore key locations in The Eternal Colony™ Universe, from ancient sites like Stonehenge and its surroundings, to the enigmatic sinkhole, each entry blends historical fact with narrative fiction. Whether you’re here to visualise the landscape, learn about the real-life locations, or uncover how the lore is woven between worlds—and maybe unearth a glimpse into the future—it’s all here. Proceed with curiosity.

Stonehenge

Image of Stonehenge by Robert Anderson, available on [Unsplash]. Used under the Unsplash License.

Stonehenge

A prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain, built between 3000 BCE and 1600 BCE. It features concentric rings of standing stones, aligned with the solstices. Its construction spanned centuries, involving long-distance transport, precise engineering, and evolving ceremonial use.

Bluestones (Preseli Hills, Wales)

Smaller igneous stones transported over 200 km from Wales, including dolerite and rhyolite. Quarried around 3000 BCE, their distant origin suggests symbolic importance. Signs reveal they repositioned them multiple times during Stonehenge’s evolution to form the inner circle.

Sarsen Megaliths (Marlborough Downs)

Large sandstone blocks sourced from West Woods, about 25 km north. These form the iconic trilithons and outer circle. Shaped with mortise-and-tenon joints and erected with remarkable precision; and dominate the monument’s visual profile.

Aubrey Holes

A ring of 56 chalk pits dating to around 3100 BCE. They may have held stones or timber posts and later, repurposed for cremation burials. Named after antiquarian John Aubrey, they mark Stonehenge’s earliest known structural phase.

- In Resurgence – The Eternal Colony™, Stonehenge plays a central role, with everything seeming to emanate from the monument. From the growing quake’s building anxiety and unrest, to the violent emergence of hundreds of megalithic stones bursting from the ground, tearing through the A303 and leaving devastation in their wake. Though unconfirmed, it’s likely the monument sits atop a potent energy source—one used to power the Sekta portal. A phenomenon electrical storm culminating around the henge plunged the region into a total electrical blackout, silencing all electronics and communications. Beneath the surface lies a replica henge, complete with an intricate map of the stars, and the precise location of the Sekta homeworld.

- Neo claims he learned English—and other languages—by listening to the countless visitors who passed through the world heritage attraction. He insists he could hear their conversations resounding through solid rock. Whether he’ll ever reveal all of Stonehenge’s secrets remains to be seen.

Durrington Wall’s

Image of Durrington Walls by Ethan Doyle White, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Durrington Walls

One of the largest known Neolithic henge monuments in Britain, located just northeast of Stonehenge. Built around 2500 BCE, it spans 500 meters in diameter, with a massive ditch and bank surrounding it. Excavations have uncovered evidence of a thriving settlement, maybe even housing for the builders of Stonehenge.

The site includes evidence of timber circles, domestic structures, and feasting remains, indicating both ceremonial and everyday use. Its proximity to the River Avon and alignment with Stonehenge suggest a ritual landscape connecting the living and the dead.

Woodhenge

Image of Woodhenge. No author named, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Woodhenge

A Neolithic timber circle located just south of Durrington Walls, dating to around 2500 BCE. Evidence of six concentric rings of wooden posts once stood at the site, mirroring the layout of Stonehenge but with organic materials. Excavations revealed the postholes, cremation burials, and a central child burial marked by a flint axe.

The monument likely served ceremonial or astronomical purposes, aligned with solstices and connected to the River Avon. Its proximity to Durrington Walls suggests it linked to part of a broader ritual landscape, bridging the realms of the living and the ancestral.

Preseli Hill

Photo by ceridwen, sourced from Geograph.org.uk. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Preseli Hills, Pembrokeshire, Wales

The smaller stones at Stonehenge—known as bluestones—originated from the Preseli Hills in southwest Wales, 178 miles from Salisbury Plain. The Neolithic people quarried these volcanic and igneous rocks, including spotted dolerite and rhyolite, from outcrops like Carn Goedog and Craig Rhos-y-felin.

Excavations revealed prehistoric quarrying techniques: inserting wooden wedges into natural cracks, then swelled by rain to split the stones from the rock face. Charcoal fragments and stone tools found at the sites date the activity to around 3400–3000 BCE.

The bluestones’ distinctive geological fingerprints match those at Stonehenge, confirming their origin. Their transport—whether by overland route, river, or raft—remains debated, but their presence suggests they held ceremonial or ancestral significance to the builders.

- Neo admitted to Ellen and Billy to having made several trips to Wales before the bluestones were relocated to the Stonehenge site. The question remains: Did he know the bluestones possessed the power to block the Sekta mind control before or after he moved them?

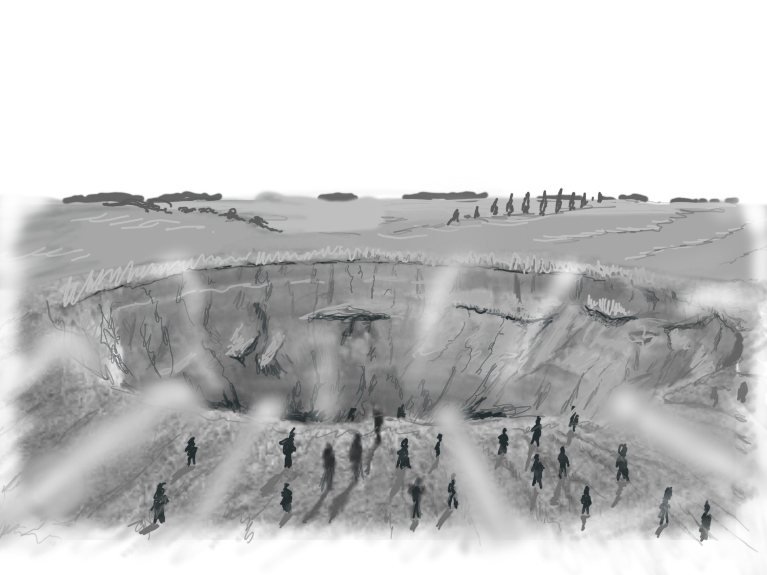

Sinkhole

Art by Jason Piggott © 2025

The Sinkhole (Resurgence – The Eternal Colony™)

Following the devastation along the A303—where hundreds of megalithic rocks erupted from the earth—the survivors experienced an illogical compulsion to descend into the newly formed sinkhole.

Its convenient gradient offered easy passage, and the people moved en masse, powerless to resist despite every instinct screaming otherwise. After a long, dark tunnel, they emerged into the greeting chamber, where clusters of lilac crystals bathed the grand cavern in an otherworldly glow.

Once the crowd was secure in the processing chamber—ready to become bug food for the colony—the Sekta sealed the sinkhole from the outside world. No one would enter again. And nothing inside would leave.

Image Description: Sketch of the survivors heading towards the sinkhole.

Vespasian’s Camp

Image: North bank of Vespasian’s Camp, Amesbury. © Ranger Steve, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Vespasian’s Camp

An Iron Age hillfort overlooking a rich landscape that includes nearby Stonehenge and the ancient cursus monuments.

Despite its name, the Roman general Vespasian has no confirmed link to the site. The name may have become popular in the 18th century because of antiquarian speculation. Archaeological surveys suggest the camp dates back to the early Iron Age, with later activity spanning into the Roman and medieval periods.

The earthworks comprise a series of banks and ditches, forming an oval enclosure. Since at least the 19th century, woodlands have covered much of the site, but it remains accessible to the public via walking paths.

Avebury

Image description: Aerial view of Avebury village. Photo by MikPeach, taken on 25 October 2009. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Avebury

Home to the largest prehistoric stone circle in the world, its vast ring enclosing part of the village itself. Unlike Stonehenge’s symmetry, Avebury’s layout feels chaotic—scattered megaliths, broken alignments, and a lingering sense of something unfinished.

The stones are older than Stonehenge, and some theories suggest Avebury was once a site of ritual contests, seasonal gatherings, or even sacrificial rites. The ditch and bank that surround the circle hint at a boundary—between worlds, or between the living and the dead.

- Neo once claimed the Sekta held gladiatorial tournaments here, pitting man against beasts like Tyakky, their oldest pet trophy. When Billy documented the cave paintings at the Lake of the Cursed, he found several depictions of these so-called contests—and recognised some of the Avebury standing stones among them.

- What happened in that arena, and who survived, remains buried in the shadows. And what lies beneath nearby Silbury Hill?

Archaeological Dig Site

Image description: Archaeological dig site. Photo by Peter Barr, taken at Hassop in Derbyshire. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 Generic.

Archaeological Dig Site (Fictional Location)

At this remote dig site, Anika, along with her best friend, Zara, whom she met at university, work alongside a team of archaeologists, uncovering fragments from the past. Among the arrowheads and animal bones, Anika discovers something extraordinary: an organic-looking artifact, resembling the antenna of an arthropod—only far larger, and unlike anything catalogued.

An hour after they sent the artifact for examination, a violent earthquake ripped through the countryside. From the fractured earth, megalithic stones erupt, as if forced upward by something deep below.

- This fictional site echoes the urgency of real-world excavations. With government plans to upgrade the A303 still on hold, the clock continues to tick. When construction resumes, we could lose countless secrets buried in this ancient landscape forever.

Mesolithic Post Holes

Mesolithic Post Holes

Discovered in 1966 during car park excavations, these three large post holes date back to the early Mesolithic period, around 8500–7650 BCE. Each once held a substantial timber post—likely pine—that rotted in place. Researchers interpreted a fourth nearby feature, lacking wood traces, as a tree-throw hole.

Their alignment and age suggest a structure or ritual marker long predating Stonehenge itself. No artifacts were found, and their purpose remains unknown.

- When Neo told Ellen his heartbreaking story of how he came to be part of the colony, he spoke of wandering away from his encampment and entering the forbidden woods in search of the mysterious totems. They marked Sekta territory, warning all to stay clear.

- Could these post holes have once housed those totems—all those years ago, when Neo was just a young child?

Blick Mead

Blick Mead

Dating back over 10,000 years to the Mesolithic Age, makes Blick Mead one of the oldest occupied settlements in Britain. Archaeologists have uncovered flint tools, animal bones, and evidence of seasonal feasting—suggesting a long-term, ritual connection to the landscape that predates Stonehenge by millennia.

The site’s natural spring maintains a constant temperature year-round, which may have drawn early humans to settle there. Remarkably, some stones found at Blick Mead are stained pink by Hildenbrandia rivularis, a rare freshwater algae that thrives in undisturbed environments—offering clues to the site’s age and ecological stability.

- Though not referenced in Resurgence – The Eternal Colony™, this could be where humans first encountered the Sekta, and the origin of the fabled stories passed on through the generations.

Bush Barrow

Image description: Bush Barrow contents on display at the British Museum exhibition on Stonehenge. Photo by Jononmac46, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Bush Barrow

Bush Barrow is one of the most significant Early Bronze Age burial sites in Britain, located just southwest of Stonehenge. Excavated in 1808, it revealed the grave of a high-status individual—often called the “King of Stonehenge”—buried with extraordinary artifacts: a gold lozenge, a ceremonial macehead, and a crafted dagger.

The lozenge’s geometric precision suggests an advanced knowledge of astronomy and mathematics. Its placement within the Normanton Down barrow cemetery ties it to a broader ritual landscape, possibly aligned with solstices and sacred pathways.

- Though not referenced in Resurgence – The Eternal Colony™, the person buried here must have achieved significant recognition. A resistant leader? a champion gladiator from the contests held at nearby Avebury? Or was it the colony that held him in high esteem?

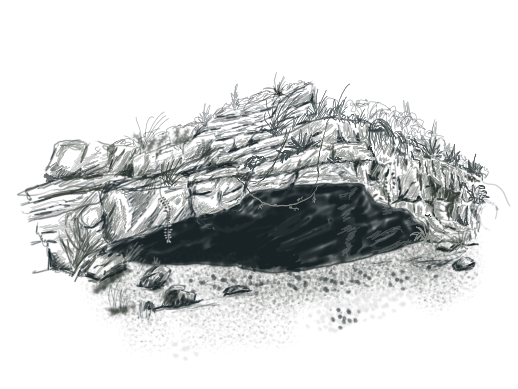

Cave Entrance

Art by Jason Piggott © 2025

Cave Entrance (Resurgence – The Eternal Colony™)

Henry was the first to discover the cave entrance—hidden in a patch of wasteland at the edge of a cornfield—while chasing after Meg, his beloved border collie. Whether it had long lain undiscovered beneath the overgrowth, or exposed by the recent quakes emanating from Stonehenge, remains uncertain.

Meg vanished into the depths, pursuing a prehistoric beast. Henry returned home shaken and dejected. After a fruitless attempt to involve the authorities, and a tense interview the following day, he descended into the unknown, determined to retrieve his friend.

Ellen, alarmed by Henry’s disappearance, convinced Billy to search for the eccentric farmer—despite lacking proper provisions, and wearing unsuitable footwear.

After the survivors who had been lured underground by the Sekta escaped, armed soldiers were stationed at the cave’s mouth. A top-secret government agency was launched to investigate and contain any remaining threat. Their mission: to prevent anything still lurking in the darkness from ever reaching the surface again.

Stonehenge Cursus

Image description: The Cursus viewed from its eastern end. The gap in the trees on the horizon marks its western end. Photo by Psychostevouk, released into the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Stonehenge Cursus

Stretching almost 3 kilometres across Salisbury Plain, the Stonehenge Cursus is a vast Neolithic earthwork—long, narrow, and aligned with the equinox sunrise. Built between 3630 and 3375 BCE, centuries before Stonehenge itself, its true purpose remains unknown.

Early antiquarians mistook it for a Roman racetrack, hence the Latin name cursus. But no wheels ever turned here. Instead, its scale and orientation suggest ceremonial use—perhaps processions, boundary rites, or ancestral observance. Barrows at either end hint at burial or transition.

- One question lingers: What part did this site play in the ancient story of Resurgence -The Eternal Colony™?

West Wood

Image description: West Woods, near Marlborough. Photo by Brian Robert Marshall, sourced from Geograph.org.uk. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

West Woods

Nestled in the Marlborough Downs, West Woods is now believed to be the primary source of Stonehenge’s towering sarsen stones. These massive sandstone blocks—some weighing over 20 tonnes—form the monument’s iconic outer circle and central horseshoe.

Recent geochemical analysis matched the composition of Stonehenge’s sarsens to outcrops in West Woods, solving a centuries-old mystery. The builders likely selected this site for its abundance of workable stone and proximity to ancient trackways.

Evidence of prehistoric quarrying, tool polishing sites (polissoirs), and sarsen extraction pits suggest the area was a hub of Neolithic activity. The nearby Wansdyke earthwork and long barrows hint at ritual significance long before Stonehenge rose on Salisbury Plain.

Winterbourne Stoke Barrow Cemetery

Image description: One of the Bell Barrows at Winterbourne Stoke Cemetery. Photo by Ethan Doyle White, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 International.

Winterbourne Stoke Barrow Cemetery

Just west of Stonehenge lies a dense cluster of Neolithic and Bronze Age barrows, aligned with an ancient long barrow and scattered across the chalk downs. Excavations revealed cremations—some in wooden coffins—alongside food vessels, bronze daggers, incense cups, flints, amber beads… and one object that defies a straightforward explanation: a piece of stalactite.

- This close to the Sekta colony, such a find cannot be coincidence. A memento from time spent in the caverns? A token of survival? The local settlers must have held the individual in high esteem to bury them here. Were they a skilled negotiator, who struck a bargain with the Sekta in exchange for… something? Or a gladiator champion winning freedom for their clan. The barrows remain silent, but maybe the stalactite can unlock the truth.

The A303

Image description: Chris, moments after the devastation. Art by Jason Piggott © 2025

The A303

The A303 is a major trunk road stretching for 93 miles (150 km) across southern England. It begins at Junction 8 of the M3 near Basingstoke in Hampshire and winds westward through five counties — Hampshire, Wiltshire, Somerset, Dorset, and Devon — before merging with the A30 near Honiton. For many, it’s the scenic alternative to the M4/M5 route when travelling from London to the South West.

The road is a patchwork of dual and single carriageway sections, notorious for bottlenecks and congestion, especially near Stonehenge. Its path cuts through the Stonehenge World Heritage Site, making it one of the few modern roads to bisect such a historic and symbolic landscape.

Plans to upgrade the A303 — including a proposed 2.9 km tunnel beneath Stonehenge — have been in development for decades. The scheme aimed to reduce traffic, restore the integrity of the ancient landscape, and improve journey times. As of July 2024, the government shelved the scheme due to budgeting constraints — though whispers persist that forces beyond bureaucracy may be at play.

- Resurgence – The Eternal Colony™

- Massive megalithic stones erupted from beneath the earth, tearing through the tarmac and throwing the A303 into chaos. Vehicles collided, tires screeched, and the air filled with dust and the sound of metal on metal. Each tremor had built in intensity until one final, devastating quake unleashed its full force—shaking towns like Amesbury and fracturing the tranquil rhythm of rural life.

- For those fortunate enough to walk—or stagger—away, the ordeal was far from over. Before the dust had even settled, each survivor felt an inexplicable urge to abandon the carriageway and descend into the vast sinkhole that had opened nearby. Though Stonehenge appeared to be the epicentre of the disturbance, newly risen megaliths clustered at strategic points across the landscape—blocking access and preventing emergency services from reaching the scene.

The Avenue

Image description: The Avenue at Stonehenge looking towards Old and New King Barrows. Photo by Ashley Columbus, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 Unported.

The Avenue

The Avenue is a 3-kilometre ceremonial pathway linking Stonehenge to the River Avon. Built during the monument’s third phase (c. 2600–1700 BCE), it follows a gentle slope and aligns with the summer solstice sunrise, suggesting ritual processions or symbolic journeys.

Farmland and roads have destroyed much of it, but traces of its banks and ditches remain. At its far end, archaeologists discovered Bluestonehenge—a ring of pits that may have once held stones, now vanished.

People still debate its purpose. Some believe the Avenue marked a transition from life to death, guiding participants from the river’s edge to the sacred circle. Others see it as a solar path carved into the land to mirror the heavens.

- Did the Avenue serve the Neolithic, the Sekta or both? We may never know.

King Barrow’s Ridge

Image description: New King Barrows, near Stonehenge. Photo by Simon Burchell, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 International.

King’s Barrow Ridge (New & Old King’s Barrows)

East of Stonehenge lies King’s Barrow Ridge, a wooded rise marked by two distinct barrow groups: the New King’s Barrows, aligned in a striking north–south row, and the more scattered Old King’s Barrows, nestled among beech trees further south. These burial mounds date from the Early to Middle Bronze Age, circa 2000–1500 BCE, and were likely reserved for high-status individuals.

The ridge offers sweeping views back toward the stones, and its alignment may have held ceremonial significance. Some early antiquarians even claimed standing stones once flanked the barrows—long since removed for road building.

Hundreds of other barrows across the Stonehenge landscape, makes this one of the densest concentrations in Britain. They come in varied forms: bowl barrows, bell barrows, disc barrows, and long barrows, spanning from the Neolithic through the Bronze Age. Each shape hints at changing beliefs, burial practices, and social structures.

Wilsford Shaft

Wilsford Shaft

Discovered in the early 1960s, Wilsford Shaft is a deep vertical pit—over 30 meters down—cut into the chalk near Normanton Down. Its purpose remains debated: was it a ritual shaft, a burial chamber, or a water source? Excavations revealed Bronze Age artifacts, including pottery and tools, suggesting ceremonial use.

Its proximity to Stonehenge and Bush Barrow places it within the sacred landscape. The sheer depth and precision of the shaft hint at advanced engineering—and perhaps a descent into something more symbolic.

- Manmade or a sealed entrance to the colony?